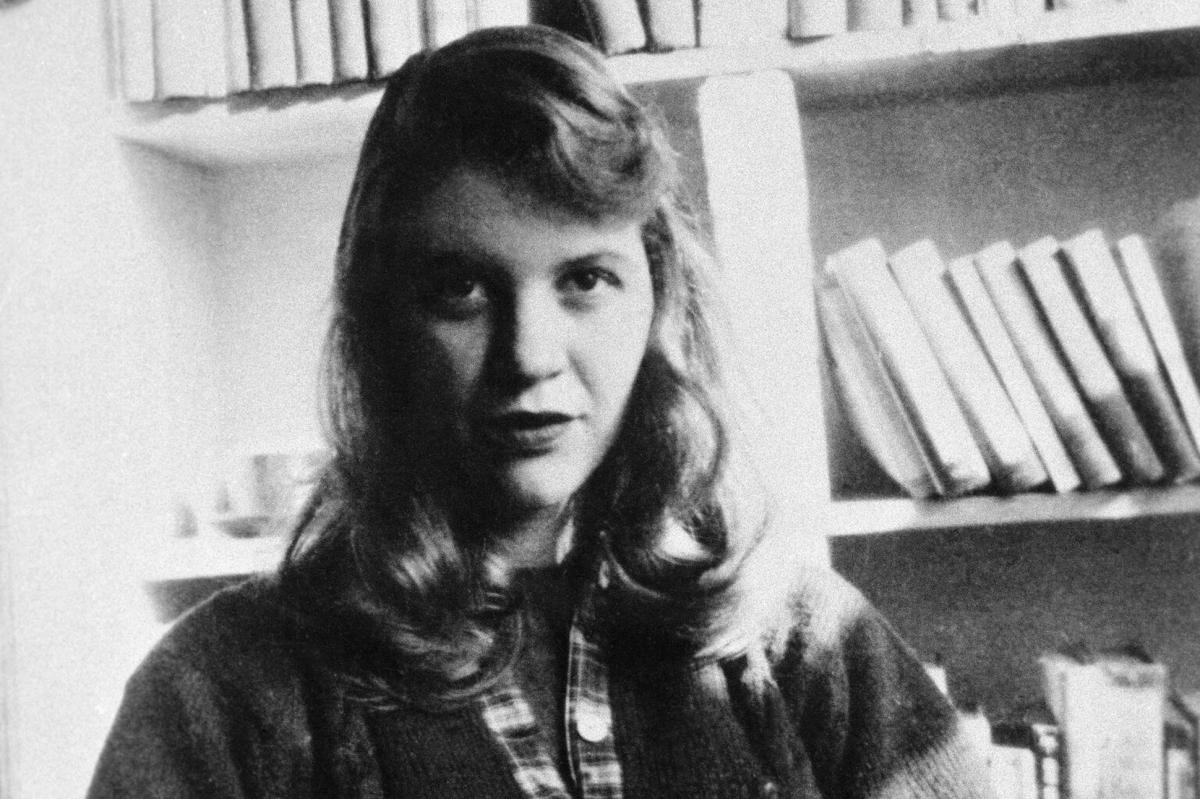

This year we were blessed with a new (to us) short story from the patron saint of sad girls and former Wellesley resident, Sylvia Plath. Plath went to Wellesley High School and then to Smith College, where she wrote the story. In January, Harper Collins released “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom,” the first new publication of Plath’s works since a posthumous short story collection in 1977.

In this fantastical and eerie story, a girl is forced onto a mysterious train ride until she makes a break for it. Plath originally wrote this story as a 20-year-old student at Smith for a class assignment, only a few months before her first suicide attempt.

“Mary Ventura” was rejected from a Mademoiselle magazine short story contest — the same magazine where she would spend a summer as a guest editor, an experience that inspired parts of “The Bell Jar.” So why have we not heard of “Mary Ventura” before? Although Harper Collins touted the story as newly discovered in promotional materials, it was actually housed with Plath’s other papers at Indiana University’s Lilly Library archives, where it has apparently been accessed by thousands of researchers since the 1970s, but was never published and therefore remained largely unknown.

Although this story is from a young Plath who was still growing as a writer, it gives us insight into her thinking at the time, and helps us to imagine who she might have become had she lived longer. In her review for The New Yorker, Katy Waldman noted that “there is a raw revulsion and disconnection” in the story. While we should not make the mistake of reading this story only as a sort of precursor to “The Bell Jar” and Plath’s more famous poetry, the author does develop that revulsion and disconnection as themes in her later works.

In “Mary Ventura,” the protagonist, Mary, spends much of the story trapped on a train, not knowing where she is going. Plath’s descriptions force us to feel the unease and sense of the room closing in on her, almost like a throughline to “The Bell Jar,” her only novel. In the novel, Plath wrote, “to the person in the bell jar, blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is a bad dream.” The bell jar and the train both trapped their protagonists, and in “Mary Ventura” we can see Plath experimenting with a dream-like, surreal kind of writing that would go on to be a hallmark of her later work.

I think anyone can enjoy reading Plath’s work and connect with it, but as Wellesley students we are in a somewhat unique position. We can read her work knowing that much of what she wrote was inspired by events that took place just a few miles away. We can drive by her house, and see the house where neighbors who provided the basis for several characters in “The Bell Jar” lived, too. She went to Wellesley High School, then on to Smith. Instead of seeing Plath as the domain of melodramatic teenage girls, we should embrace the complexity and empathy she brings to describing young adulthood. If J.D. Salinger’s ode to angsty teen boys can be taken seriously as a literary work, we owe Plath at least that much. We have the chance to read her works in a place that partially inspired them. It’s time to reexamine Sylvia Plath.