I am the daughter of immigrants. Is part of my identity, my childhood and my existence. Like many children of immigrants, it wasn’t until I was much older that I began to contend seriously with that fact of life. I of course can comprehend the clear picture of my childhood — in particular the strict East Asian upbringing that emphasizes collective identity over individuality — but with the privilege of education I saw deeper into my identity and what that should mean to me going forward in my life.

Explicitly, I want to speak of immigration, parental sacrifice and gratitude. I must admit, first, that everyone’s experience is unique, so that though one may find parallels in my words, my musings could be but faint reminders or absolute strangers to another’s own histories. Nevertheless, there may be value in these 850 words in which somebody may take solace. Thus, I write.

Sometime last year, I felt anger at — I didn’t know what. It wasn’t a stubbing-my-toe kind of anger, nor even the anger I associate with betrayal. It was, at the risk of sounding trite, much deeper than the sense of unfairness we are taught in our youth; but the roots of unfairness were there and deeply grounded. It took a certain idleness and years of subconscious thought — and a few books for the adequate language skills — for the emotions to in due time erupt to the surface.

In the midst of the political and social turmoil the U.S. was facing, I admittedly directed my anger towards my parents for immigrating to this godforsaken country in the first place, all those many years ago when my sister and I weren’t even blips in their minds. Why, I asked myself, did they do this to us?

So first I felt dry anger, and rather immediately the guilt took its place. “It was for us,” I told myself, trying, as with all other things in my life, to wash away the guilt with reason. We are told throughout our childhoods that we are lucky. We heard it from our parents, our teachers, our community leaders that we are, above all else, “lucky” as immigrants to have made it to America. There’s no greater place in the world, they told us; my grandfather has cried in front of me recalling in broken English the struggle he saw in his youth and the “good life” he lives now and how happy he is to be alive to see us, his grandchildren, live the “good life” with him. The anger is gone but the guilt has remained and will remain, to my best estimate, indefinitely.

But we were not lucky, were we? My parents and many immigrant parents in their generation worked hard to provide a life for their American-born children, endlessly sacrificing and searching for the next best thing to provide for their families. Many immigrants and their children have it ingrained in them to believe that their struggle is the requisite price they must pay for entry into a country that boasts freedom of speech and of worship, freedom from want and from fear. We are taught in our youth that we should be grateful not just to our parents but also to the people who graciously allowed us into their country. Our parents forgive and dismiss so many injustices with a strained “well we’re here, aren’t we?” Their children, myself included, grow hotheaded at the very thought of that and foster a resentment that comes spilling out much later in life. Tell me how that is lucky.

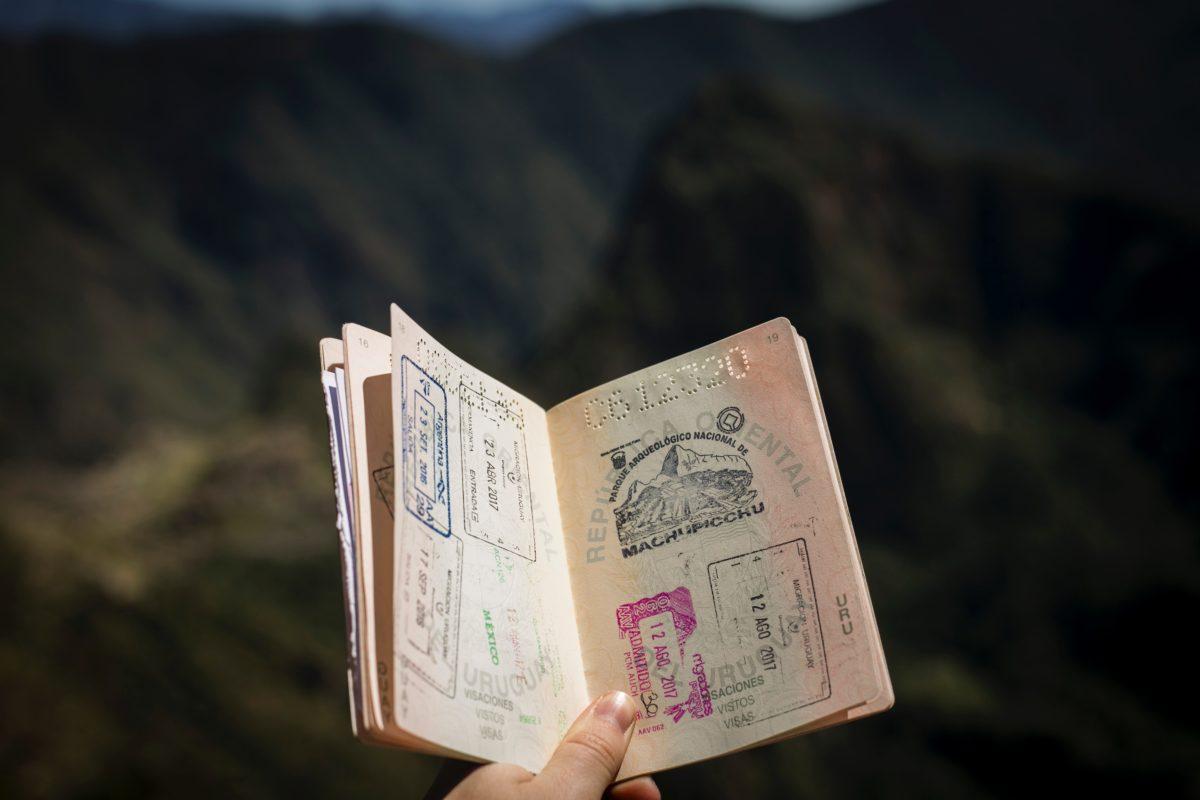

But we are here, and today I hold a U.S. passport, one of the most powerful in the world. The country may be a joke, but nobody can deny its global power. I live with so many privileges that were earned on the efforts of my parents and the other immigrants that established the institutions that provided us our voting rights, employment opportunities, religious freedoms and cultural communities. For a daughter of immigrants, I am privileged. We ride on the wave established by predecessors that have deemed us the ‘model minority,’ often failing to reflect the very term’s racist connotation; we fail in allowing it to evolve our understanding of our place in society’s race dynamics and the harm we implicitly inflict on other people of color.

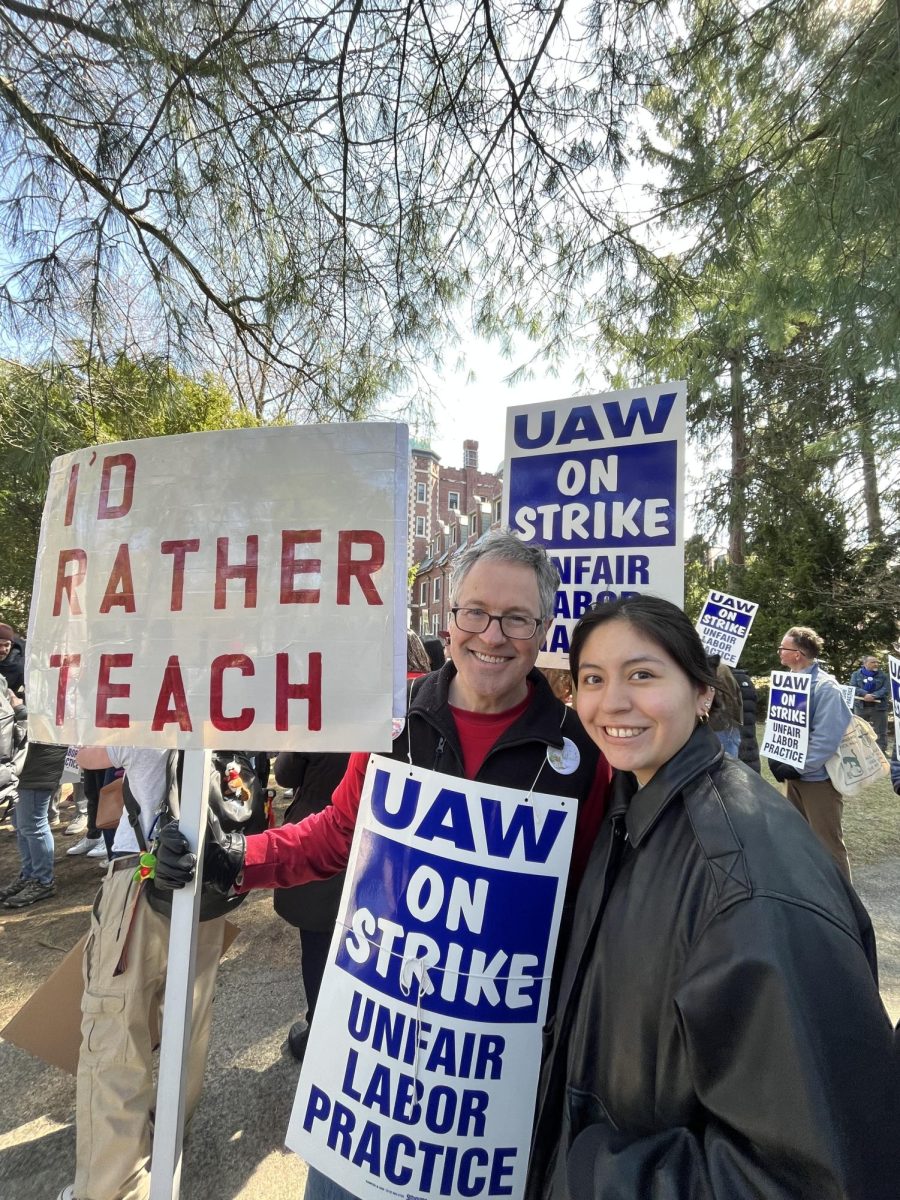

Often times I find myself thinking about the what ifs. What if I hadn’t chosen Wellesley; what if I hadn’t gone abroad; what if I didn’t write for The Wellesley News? I find myself thinking more and more, what if I weren’t American? The hypotheticals are too abstract for the confines of this piece. But there is no use dwelling on the past if not to learn from it, and moving forward for me is the sole way out of this mental quandary. I am not ungrateful for my identity and the manner by which it came to be. That said, I wish, with all my heart, that the America my parents and every other immigrant parent resettled in upheld their faithful belief in its unalienable good. In the current circumstances, American society treats each individual with irrationally conditional acceptance, immigrants of color more so than anyone else. What if we, children of immigrants, changed that?