Board of Trustees to vote on divestment in late April

While many previous student organizers had hoped that Wellesley College would be a leader among other universities and colleges in divesting from fossil fuels, as of Mar. 8, it trails behind nearly 200 academic institutions in doing so. Efforts by the ECON/ES 199 class at the College are the most recent attempt in pushing the institution’s divestment.

At the Mar. 2 Senate meeting, after months of presentations, town halls and research, the ECON/ES 199 class presented the culmination of their work: a ballot initiative aiming to increase the Board of Trustees’ likelihood of voting in favor of divestment by decreasing the overall carbon impact of the student body. Although the proposal had garnered enough votes to make it eligible to appear on the College Government election ballot in April, it still requires approval from senators in order to be placed on the ballot. The senate will vote on approving the resolution at the Mar. 9 Senate meeting.

The ballot initiative consists of four proposals: a 50 percent reduction in red meat consumption on campus, a $25 fee on mini-fridges in dorm rooms, a 10 percent increase in student parking charges and a decrease in the frequency of the school’s Local Motion bus service into Cambridge and Boston. Information about the proposals, as part of the Meeting the Moment Report, was first sent out in an email to the Wellesley College community by Chief Investment Officer Debby Kuenster on Feb. 9. The report outlines an in-depth cost-benefit analysis of each of the proposals’ costs and carbon savings calculated from Wellesley-specific data sets. With regard to implementation, according to ECON/ES 199 professor Casey Rothschild, it depends on the proposal. He adds that, for example, phasing out red meat could begin as early as next fall.

At this time, senior leadership has not publicly committed to carrying out the proposals as written, but, according to Kuenster, administration will work with students to find “a satisfactory means of implementation.”

“Should students choose to support the recommendations from ECON/ES 199, the College is committed to addressing equity issues that may arise from the adopted measures,” Kuenster wrote in a statement to The Wellesley News.

History of divestment at Wellesley

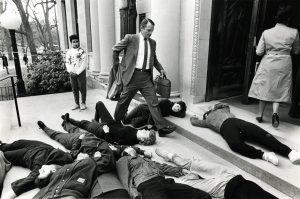

Wellesley students have called for various forms of divestment since the 1980s. It was then that students demanded that Wellesley divest from any fund with a connection to South Africa and its apartheid regime. While Wellesley partially divested from South Africa in 1985, it was not until after the 1986 protests that the College committed to fully divesting from companies that did not adhere to anti-segregation policies in the workplace (over 22 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964). Nearly a decade of on-and-off protesting peaked in 1986 when Wellesley students flooded College Road in an attempt to stop the Trustees from leaving campus after rejected divestment. 49 students were arrested that evening, with 44 remaining in custody overnight.

In 1988, students built a shanty on the Chapel Green to symbolize the inequalities facing Black South Africans. They also held rallies, lectures and vigils to protest the College’s decision to continue to invest in the country. Non-student groups, including the Radical Caucus of Faculty and Staff and the Advisory Committee on Social Responsibility to the Investment Committee, contributed to these efforts as well. Students continued to push for full divestment until the fall of the South African apartheid government in 1994.

Students moved towards fossil fuel divestment in 2013 with the creation of the student organization Fossil Free Wellesley. Between 2013 and 2014, the group organized many protests, die-ins and events to raise the College’s awareness of the urgency of divestment. In Spring 2013, the students created a petition that garnered over 850 signatures in favor of fossil fuel divestment. Members of Fossil Free Wellesley continued to advocate for change for the next year, meeting with then College President Kim Bottomly as well as members of the Board of Trustees.

In March 2014, however, the Board of Trustees rejected Fossil Free Wellesley’s request to sell off the College’s direct investments in fossil fuels. According to a statement by Bottomly, the Board of Trustees and herself did not want to use the endowment as a lever for social change. Prior to the Board’s decision, Kuenster raised concerns about the financial viability of divestment, adding that “based on my experience doing socially responsible investment…I do not think that divestment will be effective,” a factor which likely influenced the Board’s decision as well.

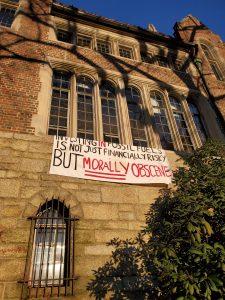

The announcement triggered the students of Fossil Free Wellesley to organize a march in protest of the decision and launch the “#RejectionDenied” campaign. In March 2015, a year after the Board voted against divestment, student organizers commemorated the decision by hanging banners around campus that questioned the decision.

The Renew Wellesley campaign began in 2018. Following in the footsteps of their predecessors, the organization led marches, protests and banner campaigns to once again call for the College to divest. The following year, the group circulated a petition, which garnered around 700 signatures, that urged 100 percent fossil fuel divestment among the Wellesley community.

In the fall of 2019, Smith College became the only Seven Sisters college to fully divest from fossil fuels. By the spring of 2020, Brown University had sold 90 percent of its investments in the fossil fuel industry. This action only galvanized calls from Wellesley students for the Board of Trustees to vote on divestment.

According to an FAQ sent to the Wellesley community by the students of ECON/ES 199, in February 2020, at a meeting with the Subcommittee on Investment Responsibility, members of the Board of Trustees stated that they would be more likely to vote in favor of fossil fuel divestment if they were shown that students would take action to promote a more sustainable Wellesley.

It’s not my job as a student on significant financial aid to help the College, with its several billion dollar endowment, to divest.

Out of these ideas came the class ECON/ES 199, in which Wellesley students worked with Rothschild to develop a full proposal to take to the Board of Trustees on fossil fuel divestment. Over the course of the Fall 2020 semester, the class gathered information on Wellesley’s carbon footprint and put together a proposal, titled “Meeting the Moment,” to present to the Investment Committee of the Board of Trustees. Work has also been done concurrently by the Sustainability Committee, which is made up of faculty and staff.

“I both see divestment is the right thing to do, and understand that it is not costless— and that those costs will be borne by the community that the endowment supports,” Rothschild wrote in a statement to The Wellesley News. “My sincere belief is that a decision to divest will be strengthened by us, as a community, recognizing those costs, and deciding as a community how we can best manage them in support of a common goal of a more sustainable world.”

Carbon Copy, a report created by the ES 300 class in 2016, found that in 2015 Wellesley emitted 45,608 metric tons of carbon dioxide. The report also notes that all the College’s emissions of carbon are “dwarfed” when the amount emitted from its investment is included. Additionally, according to the most recent Report of the Chief Investment on Wellesley’s endowment portfolio, as of June 2020, 3.7 percent, or $85 million, of the portfolio was exposed to fossil fuels. Additionally, as stated in the Divestment Resolution FAQ, divestment would cost the College between $400,000 and $1 million annually.

Student concerns and take aways

Student responses to the ballot initiative vary. While some believe that this is the College’s best chance at divesting, others raise concerns over implementation and its potential impact students. In “Meeting the Moment,” the students of ECON/ES 199 listed their own concerns for each policy that should be considered during implementation.

For Melissa He ’21, who was previously involved in divestment efforts at Wellesley, these proposals represent the culmination of years of student and faculty activism. He is the president of EnAct and worked on the Spring ’20 banner campaign. Although He said she and other members of Renew Wellesley and EnAct were initially hesitant about having a class dedicated to divestment, after seeing what the class has accomplished, the majority of the organization’s members, including He, are in support of the propositions.

“It’s not just this one class that pulled this off, it’s all of our work and all the works of students and faculty before us that has led to this,” He said. “This is finally it.”

Other students also commend the effort that has led up to this moment. However, some could not help but feel frustrated by the policies’ emphasis on individual actions. Although ECON/ES 199 addressed this concern in the Frequently Asked Questions section of the finalized ballot initiative presented during the Mar. 2 Senate, arguing that “2,400 students acting in the aggregate is no longer 2,400 individual responses,” many students still remain unsatisfied with this answer.

There’s so many things that Wellesley will need to radically change to [reach carbon neutral].

For Bella Perreira ’24, this response only raised more concerns. Perreira said the proposal “feels like shifting responsibilities of sustainability onto individuals,” and added that to her, it seemed like the response was calling for collective action in order to raise more money for the school rather than fund environmental initiatives.

“There’s no good reason for the College to also put these measures on students, and these responsibilities on students,” Alexandra Brooks ’23, an executive senator for Claflin Hall, said. “It’s not my job as a student on significant financial aid to help the College, with its several billion dollar endowment, to divest.”

Brooks, who sponsored the Senate’s original resolution to take to the Board of Trustees in December, said that she is not as upset about the individual policies, but rather that the onus is being placed on students to come up with ways to mitigate the cost of divestment when it is ultimately the College’s job. In a statement to The News, Wellesley4BlackStudents expanded on this point, arguing that the Board of Trustees is holding divestment “ransom.”

“The Board of Trustees are perpetuating the violent neoliberal myth of individual carbon footprints (which is a colonial, anti-Black and racist myth that was started by big oil companies),” the statement read. “Further, divestment is not about individual acts, especially not Black and Indigenous people’s acts, it is about industries and corporations— corporations who have been ravaging our bodies, labor, resources and sacred lands.”

Although Katie Christoph ’21 is frustrated with the burden that has been placed on students, rather than paid staff members, to come up with policies to mitigate the financial fallout, she sees the proposals as an opportunity for students to determine the costs of divestment. Christoph, a student in ECON/ES 199 and member of Renew, said she and many students were uncomfortable with leaving inevitable budget cuts at the discretion of the college. Christoph believes that no employee should be let go or fired because of proposed divestment cuts or budgetary constraints from divestment.

“Even if I disagree with the process of how it came out, I would rather [students] have a say than you get back to campus one day and your favorite dining hall staff member is no longer working there because we made a moral statement,” Christoph said.

Bella O’Connor ’21, another student in the ECON/ES 199 class, agreed with Christoph adding that another aspect of the class’s work is to hold Wellesley to the same standards environmentally as everyone else.

“A lot of times we were really frustrated. I wish we didn’t have to do this sort of thing … this [burden] shouldn’t be placed on students,” O’Connor said. “That larger frustration that the student body is feeling is also a frustration we had as well.”

The Board of Trustees are perpetuating the violent neoliberal myth of individual carbon footprints.

Students also raised concerns regarding the policies in the ballot initiative and their implementation. While Sanchez and Abby Martinage ’24 both commended the students of ECON/ES 199 for considering disadvantaged students in their proposals, they also expressed worries about what would happen when the policies went into effect. According to Martinage, many people do not have a lot of faith in administration to efficiently carry out the waiver process.

“A lot of people are stuck between wanting to suck it up and doing what it takes to make divestment happen and not wanting to get ourselves into something where people are going to be having a significantly harder time accessing rides to cross registered classes, accessing their jobs or having food in their fridges,” Martinage said.

O’Connor remarked that she believes Wellesley students will need to take part in supporting sustainability in order for the College to become completely carbon-neutral — including making personal sacrifices.

“There’s so many things that Wellesley will need to radically change to [reach carbon neutral],” O’Connor said. “Just to be frank, the College is not going to invest billions of dollars into renewable energy infrastructure if people are not willing to wait half an hour more for the bus.”

He and O’Connor are concerned that people are judging the individual proposals before reading the Meeting the Moment Report. Both students talked about how they saw misinformation — including a false rumor about the increase in parking tickets going to campus police — spreading on social media in the week following the Senate meeting. He also believes this is the College’s best chance to actually achieve divestment and that the cost of not doing so has implications for further on-campus activism.

“My biggest fear is that this doesn’t get passed, and then what else can we do?” He said. “The Board of Trustees will never take student activism seriously.”

While student support for each proposal varies, the majority of Wellesley students on social media commend the work that the ECON/ES 199 class has done.

“I understand wanting to see some commitment to making further changes towards renewability at the College from students,” Elizabeth Ray ’24, a McAfee Hall senator, said. “But I think in a lot of ways, the fact that we’ve been pushing so hard for divestment shows that we are committed to this and committed to making the College a more renewable and sustainable place.”

Ann Zhao contributed reporting.