Warning: mentions of addiction, war and death

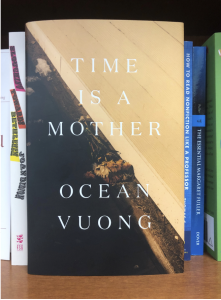

Following his poetry collection “Night Sky with Exit Wounds” and novel “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous,” Vietnamese American poet Ocean Vuong recently released his second collection of poetry “Time is a Mother” in the wake of his mother’s death in 2019. Vuong asks, “What if it wasn’t the crash that made us, but the debris?” Perhaps that’s why his writing reads like an archive rather than an elegy.

Vuong opens energetically with “The Bull,” a poem that perfectly depicts the chaos and recklessness life lends itself to. He fills his writing with imagery that demands full attention from your senses — Wonder Bread dipped in condensed milk, fish sauce, AOL chat screens and a backward wedding dress — but these moments exist alongside the traumas that ultimately shape this collection.

The opioid epidemic haunts him. (“…the McDonald’s arch, glimpsed from the 2am rehab window off/Chestnut, was enough.”) He wrestles with the memory of the Vietnam War. (“Our sorrow Midas touched. Napalm with a rainbow afterglow.”) Hills in California burn, cars crash and family members die and as he sifts through the debris of living, he paints a bleak picture of what remains.

Even moments of levity like references to Lil Peep or his picture of gravity as a blunt, annoying friend who never stops talking cannot ease the poignancy of poems like “Amazon History of a Former Nail Salon Worker,” where he chronicles the last months of his mother’s life through her Amazon purchases — pink nail polish devolves into heating pads, head scarfs and a “Son, We Will Always Be Together” birthday card.

Though he finished most of this collection before his mother’s death, his poetry bears a sense of loss that seemingly operates around her — time is marked by the months and years before and after her passing. He memorializes her dry outline in the snow in “Snow Theory” and tries to communicate with her from this side of the page in “Dear Rose.” He tells her:

“…I could not speak so I wrote myself into

silence where I stood waiting for you Ma

to read me do you read me now do you.”

“Time is a Mother” is a meditation on the disorder of American life, the relentless nature of self-destructive habits and the desire to relive the best moments in relationships, but it mainly questions whether it’s still possible to feel after tremendous loss. Vuong wants to know if his mother can read and understand his work now that she’s dead; he wants to know if losing a part of himself can make him more whole. If the world was made in seven days, he wants an eighth day to overtake him, allowing his grief to fully wash over him like a colossal wave.

Vuong’s language is heavy and thoughtfully constructed. His poems flow between lines in an outpouring of emotion, allowing us to bear the full weight of his words and their meaning as we read. He abstracts grief so it feels continuous rather than immediate, bringing us on a journey that elicits a circadian ache as he moves backwards and forwards through his memories of personal loss. In the final poem “Woodworking at the End of the World,” the narrator reflects on his life, finally receiving permission to feel. “& I was free,” Vuong tells us.