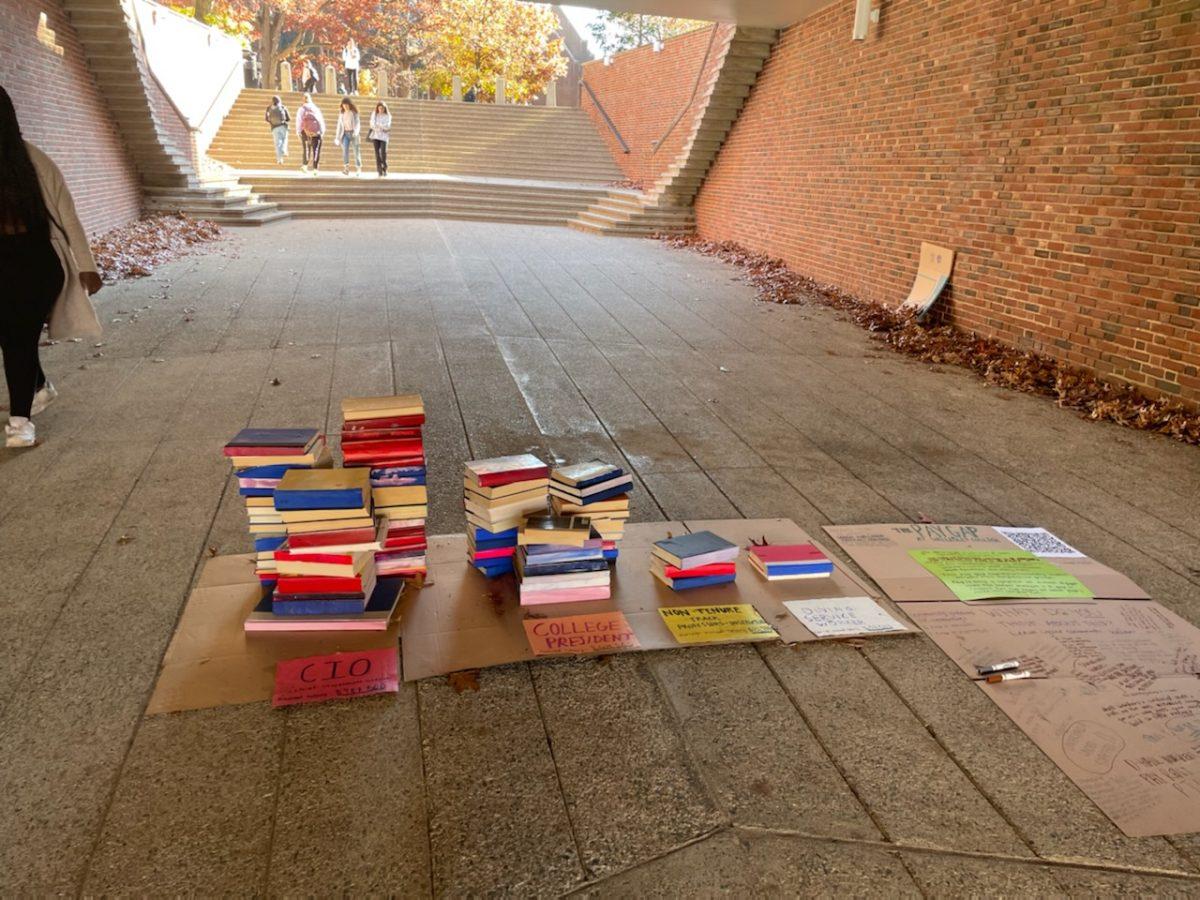

In Davis Plaza, students walking to and from class stopped to gaze at an art installation put together by a task force of Wellesley Against Mass Incarceration (WAMI) focused on Union and Labor Advocacy (UniLAd). The installation used stacks of books to visualize salary differences between the Chief Income Office, the President of the College, non-tenure track professors and dining hall workers, including salary information as well as a QR code for more information.

Hannah Grimmett ’25, who leads the UniLAd task force, oversaw the planning and process of putting up the art installation.

“We had hoped to rebuild the momentum we were seeing starting to get built last spring. We wanted something big and visual that students would be able to see and immediately understand and to feel exactly what we felt, which is outrage and confusion on how these numbers could be so extreme,” she said.

According to Grimmett, WAMI, and UniLAd specifically, works closely with labor organizations on campus, such as the labor advocacy group, American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and the union, Independent Maintenance and Service Employees Union of America (IMSEUA). Grimmett said that in receiving the salary information used in the installation, UniLAd consulted AAUP and IMSEUA through every step of collecting the data.

On the salary of dining hall staff, Grimmett explained, “Each of these salaries is honestly an overestimate as to what they’re reflecting because the starting salary of all maintenance and service workers is 80% of their full pay, and then they have to work up, over the course of four years, to actually getting their full pay. We used the full pay rate and multiplied that by the 34 weeks of pay that a dining service worker gets, and we ran that number by a dining hall service worker we were talking to to make sure that sounded accurate.”

Grimmett further explained how UniLAd obtained the salary information of non-tenure track professors, “We went to them directly and asked what sounds like a representative number, and they helped us navigate the AAUP national branch survey with average salaries in different titles. We went through and took Wellesley’s numbers and did a weighted mean between instructor and lecturer because both of those are non-tenure track professors here.”

In terms of the execution of installation, Grimmett clarified that the use of books was thematic and purposeful in drawing attention to inequities in the context of an academic setting. She also added that UniLAd realized they would need a lot of materials for the installation due to the extreme difference in salary, so they decided on books which were easy to source. Grimmett even thought about the location of the installation, in the Davis Plaza, as the perfect place because the overpass provided protection from nature, small spotlights would shine on the installation at night and many students would pass by and see it.

When it comes to the general reaction of the student body, Sofia Rodriguez ’26 said that, “Many students don’t understand the gravity of wealth discrepancy because they themselves come from immensely high-earning families.”

On faculty reactions to the installation, Professor Erin Battat, a lecturer in the Writing Program, said, “The faculty that I spoke to were really encouraged [and] inspired by the students’ creativity. I thought that the use of the books to represent the salary disparities was really clever and engaging.”

Since the teach-in on salaries of non-tenure track faculty last spring, Professor Battat, who is also the co-president of the Wellesley chapter of AAUP, believes that there has been progress towards equitable pay.

“All faculty below the rank of full professor received an across the board 5% increase in salary. Non-tenure track faculty who earned less than $100,000 got an additional 2.5% increase; those who earned less than $67,000 dollars got an additional 5% increase for a total of 10%,” Professor Battat stated. “That was significant because the College recognized that, for ‘stagnant middle,’ who were hired after 2008, the salaries were depressed and needed to be boosted.”

Professor Battat noted that, “Even the additional 7.5% that faculty that are in that middle range received is slightly less than the inflation rate. That factor diminished the actual gains from our salary increase.”

She proposed for non-tenure track faculty to have benchmarked salaries, which are consistently adjusted, so salaries become stagnant as they did between 2008 and 2020. While Professor Battat believes that low salaries of non-tenure track faculty is a key issue, she stresses that an even larger problem is the lack of professional growth opportunities.

“I would want students to connect the installation to the larger problem of income inequality in the United States, especially with people at the highest levels of a corporation earning many hundreds of times more than wage workers in that corporation. Now, the College is not a corporation, but many of us worry that it is becoming corporatized,” expressed Professor Battat.

However, she emphasized, “We appreciate and are grateful for the additional salary increases last spring, but see it as a preliminary step, and that’s because a lecturer at Wellesley still cannot afford to support themselves without the income of a partner or inherited wealth. That is directly in contrast with the mission of a college that promotes the wellbeing of women and other gender minorities.”

Rodriguez echoed a similar sentiment of dissatisfaction in the misalignment between the College’s values and issues with equitable pay, “Because of how insane our endowment is and how Wellesley markets itself as a liberal, progressive institution in order to gain more money, they have a moral obligation to use that money to make those claims a reality.”