On March 1, Sheilah Shaw Horton, vice president and dean of students, released an email update reiterating the College’s “time, place and manner” requirement of the demonstration policy and answered common questions posed by students regarding the policy

“Regarding the policy’s requirement for two days advance notification of ‘time, place and manner,’ some students want to know if this is intended to prevent protests. The answer is no, that is not the intent. Rather, we ask for this information to protect the safety of students protesting and allow for the operations of the College to continue. All of our peer colleges and universities have similar policies for this reason,” Dean Horton clarified.

While Dean Horton emphasizes that the free expression policy is meant to ensure student safety, not prevent protests, she concluded her update with a note on other methods students may use to engage with activism, if they do not want to participate in demonstrations.

“There’s a lot going on in the world right now. Some of you want to demonstrate to raise awareness and your voice. But public demonstrations are not for everyone. Some people prefer to talk in small groups to learn more and think together on strategies for engagement,” said Dean Horton.

Dean Horton’s email announcement follows recent concerns voiced by students as well as alums about the demonstration policy. The Wellesley News reached out to alums who were highly involved with campus activism during their time as students to learn more about past efforts to engage with social issues and responses from administration.

Helene Furani ’88, Elizabeth Salsburg ’86 and Sarah Arnold ’87 are alums of Wellesley College who were leaders in Wellesley’s student movement to divest from companies doing business in South Africa.

Salsburg claimed that the stark difference between social and political engagement at Wellesley and the institution she studied at during an exchange program compelled her to organize once she returned to campus.

“I did my junior year at Wesleyan through the college exchange program, and I had gone there specifically to be at a college with political activism because Wellesley didn’t have that. When I came back, it was clear we needed to be politically active, and the topic that was on everyone’s mind in the world was South Africa and apartheid. The divestment movement was everywhere but not at Wellesley,” she said.

Arnold affirmed Salsburg’s statement, “Divestment was the burning moral issue of our undergraduate years. The way that Ukraine or Gaza is now. There was moral clarity around South Africa.”

However, Furani noted that she and her co-organizers had difficulty convincing other students to join them in their push for Wellesley to divest from South Africa.

“I don’t think we were a minority in opinion on campus. We were a minority in terms of wanting to do something about it. I don’t think anybody would vocally say they were in favor of South African apartheid continuing, but it was a sort of apathy of ‘What does it have to do with us?’”

Salsburg and Arnold also felt bothered by the overall indifference they noted on campus during South African apartheid. Salsburg furthered on the importance of campus activism, “You’re not isolated and insular; you’re not just on a beautiful campus, what you’re learning needs to be expanded to the real world. Our duty as human beings is to help people.”

An article published in The Wellesley News on May 12, 2014 written by Michelle Al-Ferzly ’14, Catherine B. ’15, Dhivya Perumal ’14, Whitney Sheng ’14 and Laura Wong ’16 adequately summarizes the movement for divestment from South Africa at Wellesley College which Arnold, Furani and Salsburg helped orchestrate.

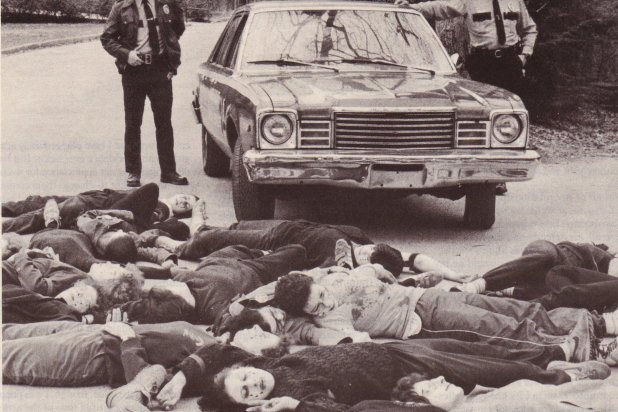

“The peak of Wellesley’s South Africa divestment movement occurred on a Thursday in late October of 1986. At their highly anticipated meeting this fateful Thursday, the Board of Trustees voted to reject Wellesley’s full divestment from South Africa. Trustee Luella Goldberg ’58 announced the vote results (17-14) on the Clapp library steps, and students stormed College Road, the main avenue that intersects the campus, hoping to prevent board members from leaving campus. Forty-nine students were arrested that evening; 44 were kept in the Natick Armoury overnight after they refused to identify themselves by their given names, choosing instead to adopt the name “Winnie Mandela” in the face of police inquiry. The “Winnie” moniker referred to the then-wife of Nelson Mandela, who was also a prominent female anti-apartheid activist.

Despite the unprecedented nature of the arrests, the students were well cared for: Wellesley business manager Barry Monihan provided students dinners from McDonalds that evening and doughnuts the following morning. Representatives from Wellesley’s administration also ensured the College community that the students were kept together throughout the night and were not separated into various Wellesley township prisons. The students were fined and released the morning following the protest, and charges were dropped as the demonstration was deemed to have occurred on the basis of “strong moral and religious grounds,” according to President Nan Keohane ’61.

Despite overwhelming resistance from the campus community, the College eventually decided on a selective divestment policy. As of 1985, Wellesley had divested approximately $1.5 million dollars from South Africa. In the aftermath of the 1986 protests, the Board of Trustees elected to divest from all companies that did not adhere to anti-segregation policies in the workplace. The College also sought to establish a scholarship fund for non-white South African students to attend Wellesley.

The divestment movement pursued its activism to fluctuating degrees over the 1980’s until the fall of the South African apartheid government in 1994. In the spring of 1988, students built a shanty on the Chapel green as a symbol of the deprivations facing the majority of South African citizens and led a series of rallies, vigils and lectures denouncing Wellesley’s remaining involvement with South Africa. In addition, several non-student groups, including the Radical Caucus of Faculty and Staff, a group of politically active and left-leaning employees of the College, and the Advisory Committee on Social Responsibility to the Investment Committee, established in 1975, continued to call for full divestment to no avail.”

“Did we accomplish our goal? Yes, South African apartheid ended. Did we accomplish our immediate goal to have Wellesley end divestment? No,” continued Salsburg on the role of activism at Wellesley in the larger movement for an end to apartheid in South Africa.

On reactions from administration and faculty, Arnold expressed, “Faculty by and large supported us, at least I never heard faculty speaking out against our efforts. Nan Keohane supported us, not always, not everything that we did, but we felt like she was kind of on our side, at the same time respecting that she was in a tricky position as college president. … I think we got very lucky in that the administration was pretty darn liberal.”

All of them expressed that they never felt opposition from administration, more so from the Board of Trustees.

“Even though Nan Keohane didn’t come out supporting us, she made her administration very available to us. We didn’t break and enter, we entered. Someone from admin happened to leave the phone out, so we took over the office wing; [Furani] was able to talk to the press from this phone. We were supported, but we were supported quietly,” Salsburg commented.

Furani corroborated, “The trustees’ approach was, ‘Oh, you little girls, you don’t really know anything,’ that we were naive or we didn’t have any authority to speak. There was a different approach from administration and faculty. They liked to see us taking on roles of leadership and were very sympathetic to our asks, with a sort of protective mentality.”

When asked about Wellesley’s most recent policy on free expression and demonstrations, Arnold commented, “I can see where they’re coming from on that. At the same time, I can also imagine that it becomes a real topic of debate whether or not you feel the need to respect them depending on what you want your action to accomplish.”

She also noted that no such policy existed when she was a student. “They just had to put up with us,” Arnold said.

Additionally, Arnold questioned if the “time, place and manner” requirement impacted the effectiveness of campus protests.

“Does that mean the general campus community can know before and can avoid that area? I wonder how that works especially when you’re trying to shock fellow students out of apathy, wearing their blinders and only thinking about their next exam.”

Arnold, Furani and Salsburg all expressed that their role as student organizers when at Wellesley is something they still carry with them decades after graduating.

Salsburg shared, “Those of us who were activists then are still activists now on a small level. There are different versions of activism. I happen to be a pediatrician in California, and I very consciously made sure that the practice I work in takes patients who are on Medicaid. I was also involved in setting up a medical clinic for adults who were in the foster care system or previously unhoused. [There is] a lot of marching and signing protests for causes, it continues … ”