What is the future of democracy?

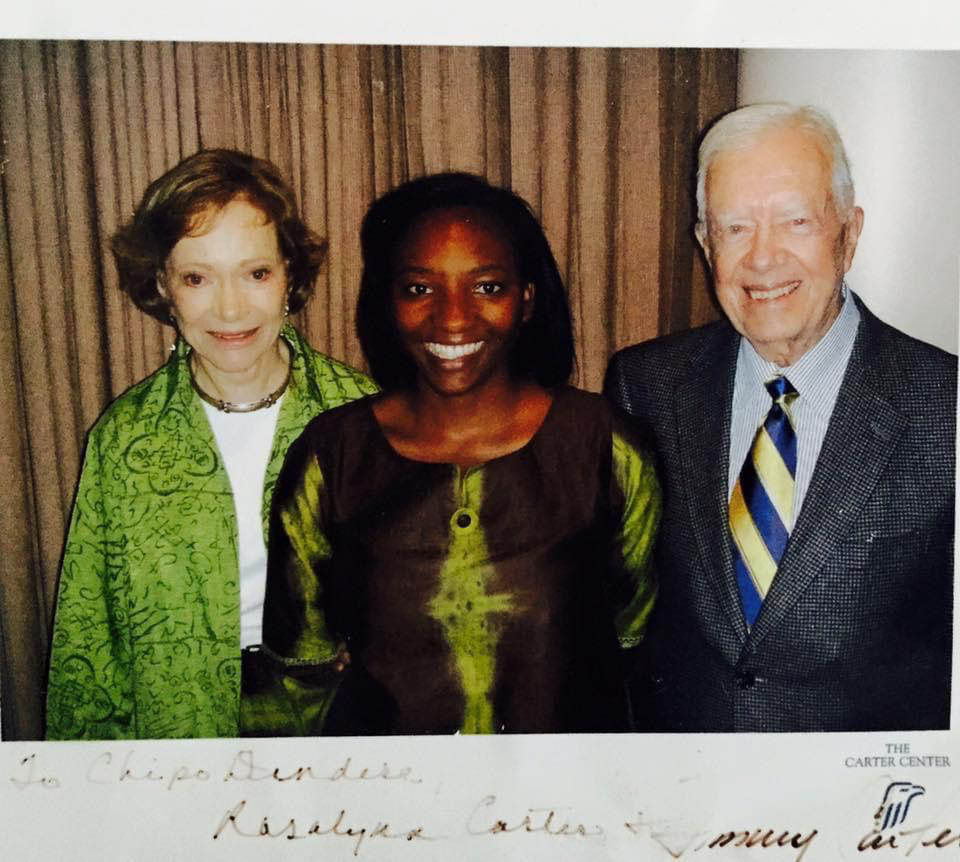

In January, at memorial services for President Jimmy Carter, most people asked me about the state of democracy on our campus. When they learned I was born and raised in Zimbabwe, they inquired about inflation and autocracy there.

My responses varied because my thoughts on the future of democracy and autocracy continue to evolve. I am slightly more optimistic than many scholars of democracy. Some, particularly among the younger generation, perceive democracy as in crisis and feel a sense of doom. Even President Carter expressed concerns that democracy is in jeopardy.

These pessimistic views are rooted in the reality that, recently, politics seems more toxic and dangerous in the United States and worldwide. In Africa, leaders are demanding to extend their presidential terms. There is a growing shift toward the right in Europe.

I have little professional reason to feel optimistic. My forthcoming book has a rather grim title: “Death, Diversion, and Departure: Voter Exit and the Persistence of Autocracy in Zimbabwe.” As a Black immigrant woman, not much about my existence on this campus or in the world inspires optimism. Despite this, I feel less pessimistic than I might.

First, as a Wellesley College professor, I have a front-row seat to observe, educate and learn from the future — our students.

Second, I get to engage with brilliant colleagues — our goal as the inaugural Hillary Rodham Clinton Center (HRCC) faculty fellows is to create more dialogue spaces. We may not always agree, but we are committed to the good fight.

Finally, growing up in an autocracy has shaped my worldview and allowed me to appreciate the complexity and precariousness of open dialogue. I want to share how that painful experience has given me the perspective to remain hopeful about democracy. I do not think I have any option but to keep faith that even a flawed democracy is still our best and only option.

Growing up, I did not know Zimbabwe was an autocracy. I was protected from this knowledge as a Shona middle-class child. Other children were forced to learn much earlier about the dangers of the ruthless regime of Robert Mugabe.

Even so, I witnessed the little everyday wars that come with living in an autocracy. One of my earliest political memories is attending a rally with my parents. Landowners in our town were forced to attend — if they did not toyi-toyi to the regime, they would lose their land or even their lives. At age six, I did not understand the gravity of this situation, so I “accidentally” started the car and nearly drove into the crowds. My stepfather joked that I had saved them from listening to a boring speech. My mother was less amused; she still worries I am too vocal, too direct in my criticism of the Zimbabwean government.

In my first year of high school, my beloved stepfather died. He was my hero. He instilled in me the importance of honest and open dialogue even when it is difficult. When he died, I could not go to his funeral. The Zimbabwean government had created a militia for its land grab projects. The militia was also available for hire by people who wanted to terrorize widows, who had no property rights. My widowed mother had felt it was too dangerous for me to return home and bury my dad. When I eventually returned home from boarding school, our home resembled a scene from a war movie. This was when I became radicalized in my feminism and belief that countries need strong democratic laws.

By the 2000s, I was a sophomore in college in Oregon, 10,000 miles away from home. It was not until then that I learned about the 1983 Gukurahundi genocide of over 20,000 Zimbabweans. It took me a long time to forgive myself for not knowing about something that not only happened before I was born but that our government censored heavily. I am eternally grateful to friends whose families were impacted and through whom I have gained more understanding of such atrocities. These lessons fuel my commitment to a better Zimbabwe for all.

And Zimbabwe was still burning. The government was forcing people from their homes, the economy was in free fall, and opposition politicians were dying if they did not flee.

Two decades later, my life has changed. I am a married professor and mother, yet the Zimbabwe crisis rages on. Autocracies are stubborn in their longevity.

Growing up in an autocracy taught me that we do not have the luxury of giving up. College campuses are essential in preserving democratic values. Our job is to engage in debate and learn from one another. I tell my students that their Wellesley siblings may be some of the most important people in their lives. I hope our campus continues to be a place for rigorous debate and exchange, where we listen to each other and build strong relationships.

I remain optimistic that democracy is not in peril as long as you and I are willing to dialogue and learn from each other.