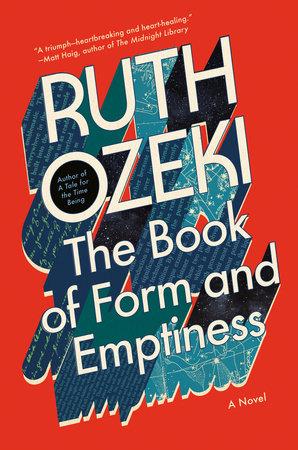

Ruth Ozeki, filmmaker, novelist and Soto Zen Buddhist priest, visited the Newhouse Center on Nov. 7 as part of a book tour for her most recent novel “The Book of Form and Emptiness,” which won the U.K. Women’s Prize for Fiction. In addition to writing, she teaches at her alma mater Smith College as the Grace Jarcho Ross 1933 Professor of Humanities in the Department of English Language and Literature. “The Book of Form and Emptiness” is her fourth novel, building upon the themes of personal experiences and socio-political issues found in “My Year of Meats” (1998), “All Over Creation” (2003) and “A Tale for the Time Being” (2013). She has received numerous accolades for her work, both film and novels, and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for “A Tale for the Time Being.”

She truly missed being able to go on tour and was delighted to read a few short passages from the novel before talking more in-depth about it. In fact, voice is central to the structure of the book, as the book itself is one of the narrators, creating a dialogue between Benny, the main character, and it. Not only does this create an unreliable narrator, but it brings a playfulness to what would otherwise be a difficult narrative to read. Benny, a 14-year-old boy, is struggling with the recent death of his father as well as what ends up being diagnosed as schizo-affective disorder. He begins to recover through reading, not unlike Ozeki herself.

She said that “fiction has to be the most personal genre,” as her novels have all included some sort of personal element to them. The most recent two have featured teenagers struggling with mental health and finding solace in books, similar to how Ozeki coped with anxiety and depression at that age. She was also processing the death of her own father during the course of the eight years it took to write the novel. She said that is in part why there are so many personal elements, as her political opinions cannot help but be infused when she has time to ruminate on them. It becomes a positive feedback loop, however, where she struggles to finish when there are more ideas to incorporate because she takes more time.

In addition to the personal exploration in “The Book of Form and Emptiness,” Buddhism played a big part in shaping the novel. Ozeki drew from a question from a Zen parable “do insentient beings speak the dharma?” to inform how inanimate objects’ voices were incorporated into the story. Dharma roughly translates to “right way of living,” and could refer to how the inanimate objects form attachments to people and vice versa. This was combined with the proverb “only a Buddha in a Buddha” — meaning no enlightenment without others — when she chose to feature multiple perspectives in the narration. It felt limiting to only have the third person omniscient narrator, as initially she was just writing from the book’s perspective. She later switched to incorporate Benny, however, finding the two together to convey her themes better than the one. Finally, Ozeki centered the relationships that Benny formed, especially with those who were also receiving treatment in the psychiatric inpatient ward, as a way to illustrate the Buddhist concept of “no self.” Benny couldn’t begin recovery unless he had the support of others. While the novel itself is a complex read, understanding how Buddhism is interwoven into the text adds a layer, giving more food for thought.