“Did you have a clear idea of what you were going to do on set?” Francesco Alò, film critic for the Italian digital magazine BadTaste, asks director Luca Guadagnino in an interview for his newly-released film Bones And All. “Always,” says Guadagnino, as a sly smirk creeps onto his face, “inevitably — it’s my way of being.” Alò, disarmed and speechless, chuckles in response.

Guadagnino doesn’t lie — not now, at the height of his international fame, and not before, as an aspiring filmmaker born to an Italian father and Algerian mother in Palermo, Sicily. And the director’s muse, Tilda Swinton, the figure that has accompanied the entire trajectory of his career, can testify. In 1994, Swinton was visiting Rome for a showing of Derek Jarman’s work in Palazzo delle Esposizioni — a grandiose, off-white colored gallery at the top of a wide staircase leading into the trafficked Via Nazionale. Guadagnino had previously tried to reach Swinton and offer her a role in a short film he had written. Through the crowd of the exhibition, Guadagnino, who lived in Rome at the time, walked up to the Hollywood star to ask her why she hadn’t responded. Guadagnino knew what he wanted. Looking back, Swinton tells The New Yorker that she was “massively and instantly caught in the genius of his guilt trip.” From that moment, the two clicked and Swinton has described their relationship — the British actress has starred in four of Guadagnino’s pictures, from The Protagonists in 1999 to Suspiria in 2018 — as one between “a pair of six-year-olds in a sandbox,” according to The Guardian. As six-year-olds do, Guadagnino plays, destroys to build again, invents — “e’ un gioco,” says Guadagnino in the same interview with Alò, describing his new film. It’s a game.

Guadagnino’s Bones And All, starring emergent Taylor Russell and Hollywood veteran Timothée Chalamet is currently in theaters. Based on Camille DeAngelis’ 2015 novel of the same name, Bones And All is Guadagnino’s first film shot entirely in the United States and revolves around two cannibals — a metaphor for two tormented, isolated souls — who fall in love as they find solace in protecting, or merely accompanying, one another’s cursed solitude. Guadagnino’s camera appears to frame and elevate the decadence of the Americana — an abandoned warehouse here, a gas station there, a convenience store in a town forgotten by God — with the same grace as a mind-altering, gourmet prawn dish in I Am Love (2009), a swimming pool during Pantelleria’s scirocco season in A Bigger Splash (2015), and an orchard in the Northern Italian countryside of Call Me By Your Name (2017). As described by Swinton herself, Guadagnino builds a “sense-ationalist” cinema, finding its force in the senses it exudes and, in turn, provokes.

Guadagnino’s A Bigger Splash, to me, exemplifies his style. His remake of Jacques Deray’s 1969 La Piscine holds all the things that fascinate the director — deceit, art, the past encroaching on the present, music, betrayal, and, of course, Italy.

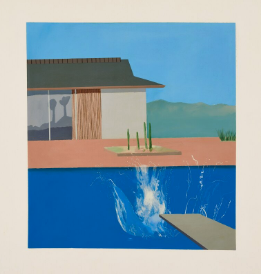

In David Hockney’s 1967 painting that inspired the title, and maybe even the essence, of the film, a splash erupts from a pool in front of a house in the desert. The water surrounding the splash, however, remains in an unnatural, immoble equilibrium — an effect without a known cause. The house’s sliding doors reflect objects above the pool that we, as viewers, can’t see and, in turn, can’t trust to really be there.

Guadagnino follows suit. In A Bigger Splash, the main characters — a cast adorning the names of Tilda Swinton, the protagonist, Matthias Schoenaerts, Ralph Fiennes and Dakota Johnson — are the reflections in Hockney’s painting. They’re there, but not really; they’re there, but not for the reasons they say are; they’re there, but they’re not who they proclaim to be. While some more than others, they’re all rotten. They move through the dry, asphyxiating winds that ruffle the Sicilian island of Pantelleria and, blown by a sudden gust, fall into a game of brinkmanship, infidelity and violence. As the film begins to reveal a nation’s skeletons in its closet — from Italy’s racism, the xenophobia studded in its colloquial, day-to-day routine, to an almost prophetic corruption in favor of the élite —, those of its characters begin to unveil in conjunction. As mentioned before, Guadagnino knows Italy — if Call Me By Your Name made everybody want to buy a one-way ticket to Italy, A Bigger Splash makes you book the return.

The “horrific,” then, and its various manifestations, seems to have inhabited all of Guadagnino’s films long before the arrival of Bones And All. And, perhaps, Guadagnino’s versatility of genre resides in this — in the fact that the “horrific” can appropriately reside in all places, from the emergence of a sculpture of Venus in Lake Garda to two lovers escaping a shared curse across a rural, barren American countryside.

If you’re not faint of heart, I’ll see you at the movies.