Disclaimer: contains spoilers

Wonder Woman 1984 is not a women’s empowerment movie; in fact, it has exactly the opposite effect. It is a franchise made for the external and internal male gaze. Wonder Woman is one woman who is above all other women, yet still passionately loves one (dare I say mediocre) man. Wonder Woman is, biologically speaking, not an actual human, and is far too perfect, a notion that is displayed through comparing her with other women.

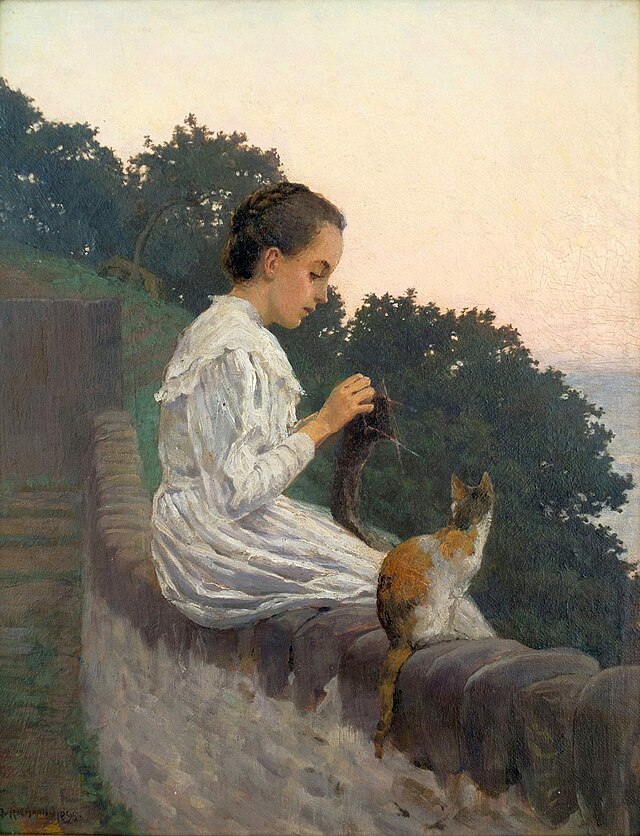

Despite not being from the mortal world, Diana Prince (Gal Gadot) conforms perfectly to society’s standards of performed femininity. She has tremendous strength and had years of athletic training since birth, yet her body is extremely slender, “sexy,” hairless, with very little muscle tone. Looking at the strongest and most agile women of the world — Olympic athletes, powerlifters, gymnasts — the difference is stark. Her Wonder Woman outfit includes a pair of heeled boots, which are inconvenient for running and damaging to the spinal cord and pelvis — scientifically and athletically, it does not make sense at all. Her hair is always perfectly curled and she always has makeup on. In the first movie, her infantilization bothered me: being new to the human world, she was oblivious to her beauty, to her effect, and she had to completely depend on the male lead to help her navigate the world. As a result, she seemed even more beautiful in the male gaze, because confident women who are aware of their beauty and power threaten the patriarchy.

In Wonder Woman 1984, the villain of the movie is a woman named Barbara Minerva (Kristen Wiig) who becomes her comic-book counterpart, Cheetah, when she receives superpowers. Barbara is an archetype: a clumsy, nerdy woman who cannot grapple with feminine standards: she cannot walk in heels, her hair is a mess and she cannot get any guy’s attention. Despite holding three degrees, being highly intelligent and conforming to society’s beauty standards by being a skinny white woman, her foremost concerns are with her looks, ability to be sexy in heels and male attention. She falls victim to the internal male gaze. When she meets Diana, she immediately wishes she could be her. The camera pans to Diana’s tall animal print heels (foreshadowing for Cheetah?) contrasting them with Barbara’s shorter heels that she struggled with. One of the first noticeable differences after Barbara gains powers was her newfound ability to walk elegantly in heels.

Barbara’s jealousy of Diana turned her into an evil supervillain. She is literally stripped of her humanity — she becomes an animal. She ends up putting all her life’s academic achievements and the fate of the world behind that envy. In fact, the very cause of the apocalyptic disaster is because she was naive enough to be tricked by a man who gave her validation for the first time ever. Barbara’s character exists as a total foil for Diana — the only point of her character is to show how perfect and virtuous Diana is in comparison.

Barbara is clumsy, vain, envious, too easy, selfish, while Diana is a moral beacon, beautiful but never vain or aware, only loves one man loyally, powerful but not explicitly so, inhuman yet conforming, forever young. She is a “cool girl,” an exception among women, because good women are the exception, must be an exception, to uphold their general inferiority. Even after 70 years, she has not gotten over her one true love’s death, the first man she ever met and ever kissed. In my opinion, this foretold lover, Steve Trevor (Chris Pine), does not really have a personality, beyond liking airplanes and loving Diana. (The bar is low, y’all.) She had an incredibly hard time giving him up, even when saving the whole world is on the line. Yes, the central point of conflict for Diana’s emotional growth in this movie is about a man.

Adding two scenes of beating up a male harasser does not make this a feminist empowering movie. While movies featuring women do not have to be feminist, it was still marketed in this manner, which makes it highly insidious. This entire franchise is marketed for empowering young girls, yet how can it be empowering to young girls if it is literally impossible to be Wonder Woman? How can it be empowering when the point of this movie is showing the type of “correct” and perfect woman to strive towards? This movie promoted competition between two wonderful and intelligent women and villainized an imperfect, complex human woman. Internal misogyny is something most women have to confront, and capitalizing off of that emotional process for the male gaze is something I will never support.

When I asked my friend, who loves Wonder Woman, why Diana wears heels and has perfect hair while hurtling through the air, she simply answered, “because she’s perfect.” And in my mind, perfection is the antithesis of liberation. I would not recommend this series to anyone.

Campbell | Mar 20, 2021 at 2:43 pm

Great work, Grace. I would only point to the adjacent conversation about The One. Perhaps, the most isolating and least-inclusive element to these sort of action/fantasy extended stories is the idea of The One. Diana Prince is the savior of her people, not because of her beauty, her strength, her prowess, or her intelligence, but by some miracle of birth. Most stories in this vein include some protagonist who is important to the story for reasons outside their agency. They may even resist initially. They’re born with some innate ability to solve some grand problem or defeat some malignant enemy, more from nature/god/chance granting them a power no one else has than any quality any reader/watcher may possess. Harry Potter. King Arthur. Neo in the Matrix. Luke and Anakin in Star Wars. Superman. And so many more. This serves mainly to distance us from the hero inside us. Why act if we weren’t born special? Why act to improve if the key to success lies in the luck of draw? There are elements of Diana that are impressive –her strength, her willingness to confront evil– but they stem mainly from her inherited role as the “god-killer.” She’s not just a regular Themysciran, and this is a problem. How can she ever be brave if she’s perfect?

There are some hero stories, even in the comics genre, that sidestep this, and they are usually less problematic for it.

Thanks for this piece. Youi rock.