Content warning: mentions of spoilers and homophobia

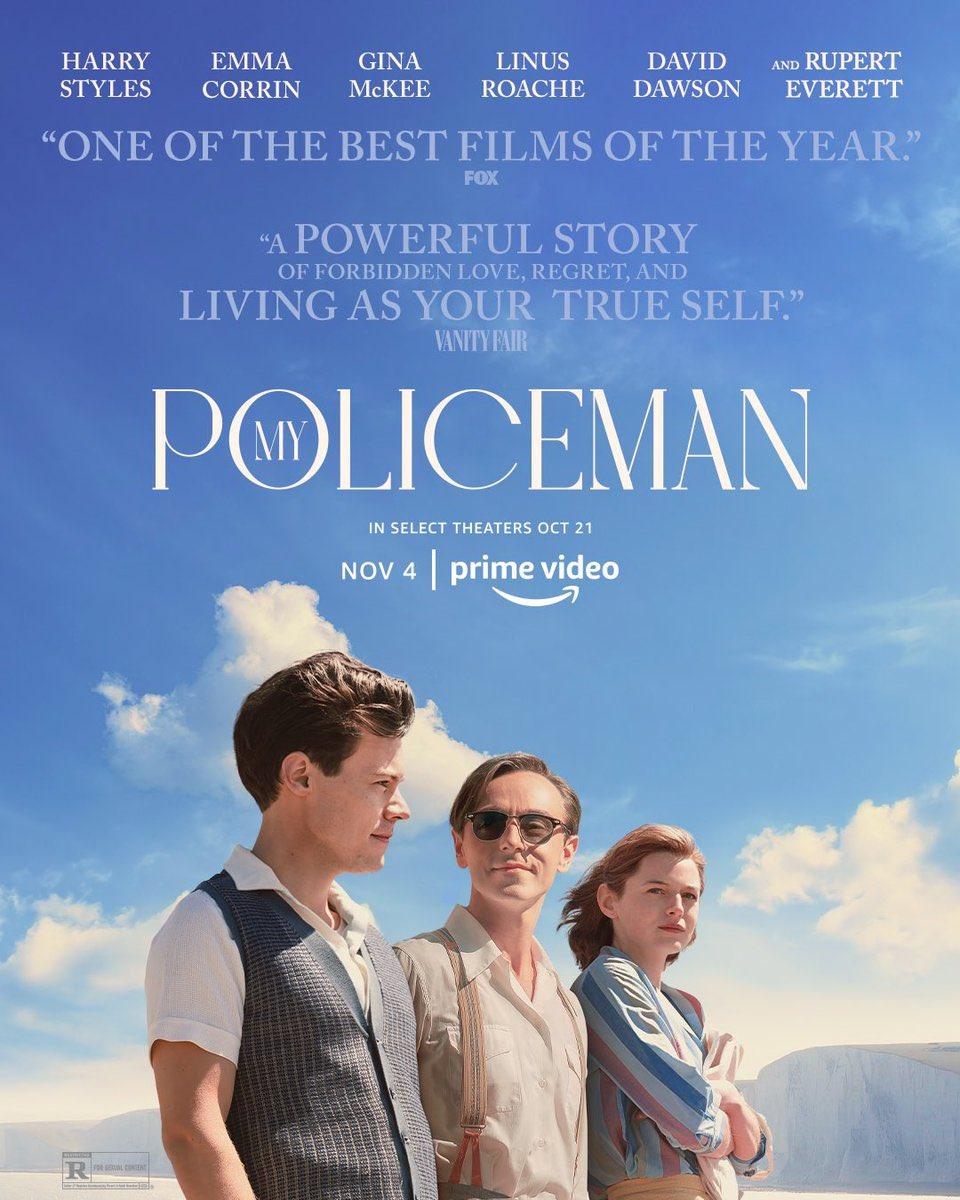

Grandage, the film explores the relationships Tom, a policeman, has with the two people who know him as “my policeman” — his wife Marion and his lover Patrick — across two timelines: the past in Brighton in the 1950s, and the present in Peacehaven in 1999.

The novel’s narration shifts between Patrick’s diary entries from 1957 to 1958 and Marion’s recollections in the present, which she records as a means of confession after Patrick moves in with her and Tom following a stroke. The interiority of the two narrators is not a quality that transfers easily from page to screen, and translating the nuances of such complex and raw emotions is a challenge that both shapes and scars Grandage’s adaptation.

As in the novel, the film opens in the latter timeline in 1999 where Marion (Gina McKee) prepares the guest room for Patrick (Rupert Everett), Tom (Linus Roache) walks the dog by the ocean nearby and Dean Martin’s “Memories are Made of This” plays to liven the otherwise muted house. But this somewhat cheerful beginning feels at odds with the novel’s startling opening lines. “I considered starting with these words: I no longer want to kill you,” writes Marion to Patrick, the intended recipient of her confessions.

In the novel, the plot is partly driven by her letter to Patrick — a narrative choice that provides insights into her desires, motivations, and justifications — but the film does not employ her as a narrator on screen or through a voiceover, and there’s no visual rhetoric that mirrors her confessional writing style. That the film breezes over Marion’s early infatuation with Tom, which began after she befriended his sister SylvOn Nov. 4, 2022, Amazon Studios released “My Policeman,” a film based on Bethan Roberts’ 2012 novel of the same name about love thwarted by betrayal and homophobia. Directed by Michael ie in grammar school and never truly ended, is another loss.

In the film, the earliest flashback to the 1950s takes place after Tom (Harry Styles) and Marion (Emma Corrin) have already settled into their careers, as a policeman and teacher respectively, and there’s no reference to their childhood connection. During the scene where Sylvie (Dora Davis) notices Marion pining after Tom, rather than implying his attraction to men by telling her that “Tom’s not like that” like she does in the novel, she says that he likes “loud, busty types,” which rattles but does not confuse Marion.

Roberts’ language has depth — yearnings, fantasies and an act of duplicity that has lasting consequences. Grandage’s direction is appropriately romantic and emotional, but it often smooths out subtle expressions of affection. For example, in one of the first moments of connection between Tom and Patrick in Roberts’ novel, Patrick, an artist and curator at the Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, shows Tom his favorite part of the museum’s collection: a painting by J.M.W. Turner. But the two men don’t just look at Turner’s image of crashing waves and pounding foam – they absorb it. Like conspirators, they whisper observations and sneak glances, considering each other the way others in the room consider the artwork.

The scene appears in the film with some modifications. In the museum, Patrick (David Dawson) finds Tom (Styles) staring at Turner’s “Snow Storm — Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth,” providing a face to the unnamed painting in the novel. The two men still discuss the masterpiece, commenting on the strength of the waves that simultaneously excite and frighten them, but there’s no whispering or subtle glancing. The scene, which still feels intimate, ultimately describes rather than confides, which reverses the approach of the source material.

Many of Grandage’s interventions also soften the unreliability of the two narrators by giving us glimpses of Tom, a dreamy cipher whose point of view is excluded from the novel, simply existing in scenes without Marion or Patrick. In the 1950s timeline, he smokes on the beach to calm his nerves before heading to Patrick’s apartment for the first time, and he burns his uniform after Patrick’s arrest. In the 1990s, he stands in the doorframe to watch Patrick sleep, and he cries in the car after he sees a gay couple holding hands in the grocery store. He becomes less of a projection of others’ desires and more of a dynamic character.

As beautiful as the film is, it never captures the rawness and psychological precision of Roberts’ novel – the recollections of the past, the admissions of guilt and regret and the sound of Marion’s and Patrick’s voices in our ears. “My Policeman” is a story about many things — 1950s British politics, postcards from Venice, repressed emotions and lost time — but it’s mainly a meditation on the devastating outcomes of homophobia that crash against the three characters in waves of pain that never dissipate.