Like the Victorian version of the frats of Beacon Street on Halloween, members of Gilded Age high society “pulled up” in elaborate costumes to 660 Fifth Avenue, the lavish New York City mansion of the Vanderbilt family. In 1883, Alva Vanderbilt threw the most extravagant costume ball the city had ever seen, which served as a critical battleground in the civil war raging through the rich families of New York. Alva used the ball as a 6 million dollar (in today’s money) maneuver to force old money “it-girl” Caroline Astor to accept the “nouveau riche” Vanderbilts into established high society.

The Vanderbilt family’s seemingly endless railroad fortune meant that no expense was spared (champagne alone blew $1 million of the budget), and guests were expected to do the same for their attire. Though costumes ranged from vaguely historical to grotesque to racially questionable, the common denominator was the unabashed spectacle of decadence. It’s crucial to keep the historical context of the Vanderbilt Ball in mind and view the Ball’s costumes with an air of critical appreciation, striking a balance between appreciating the intricate artisan work, painstaking craftsmanship and sheer beauty of these elaborate costumes while also being critical of the tone-deaf lavishness, exploitation and wealth inequality woven into the fibers of these garments.

Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt as “Electric Light”

(José Maria Mora, Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt as ‘Electric Light’ at the Vanderbilt Ball, 1883. New-York Historical Society Library.)

Worn by Alva Vanderbilt’s sister-in-law Alice Vanderbilt, this costume was designed by leading couturier Charles Frederic Worth. It paid tribute to the marvel of the electric lightbulb while also referencing the iconic pose of New York’s Statue of Liberty. It was first displayed in Manhattan’s Madison Square Park in 1876. Gold thread and silver tinsel were painstakingly embroidered by hand onto yellow satin in a lightning pattern, and, most remarkably for the era, a battery was sewn into the dress in order to light up her handheld torch.

Alva Vanderbilt, though triumphant in her victory over Caroline Astor, was outshined by her sister-in-law Alice’s Electric Light costume, which almost certainly threw a damper on her celebratory mood.

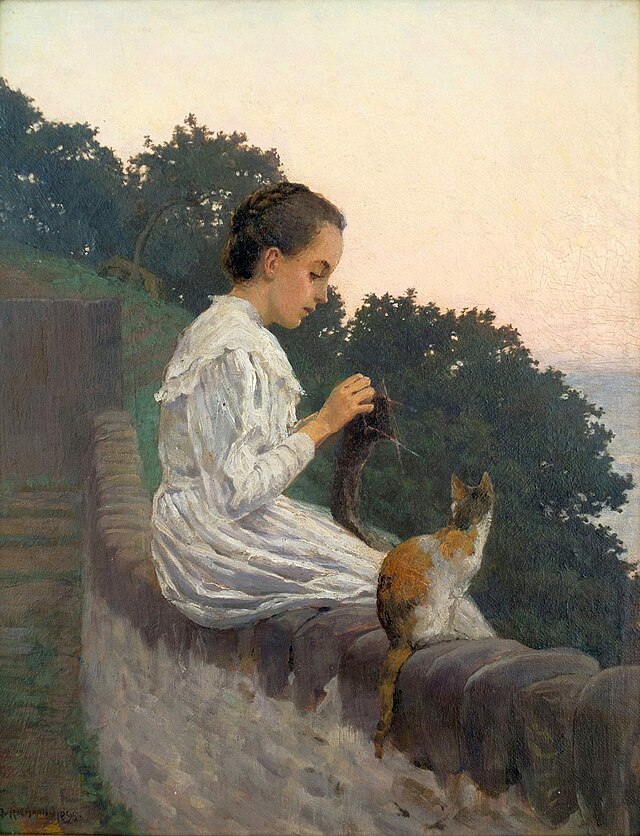

(Mora (b. 1849). Miss Kate Fearing Strong (later Mrs. Arthur Welman). 1883. Museum of the City of New York. F2012.58.1460.)

Just “Cat” was Kate Fearing Strong’s costume. It was completed with what The New York Times reported as “a stiffened white cat’s skin” on her head, an overskirt made of white cats’ tails, and a bodice with rows of white cat heads. What’s on her neck? A midnight blue choker with a bell dangling from the center and inscribed with “Puss,” allegedly a reference to the wearer’s nickname.

(A woman dressed as a goose at the Vanderbilt Ball, 1883. New-York Historical Society Library.)

Continuing on the taxidermized-animal-as-headwear train, an unidentified woman came dressed as “Goose,” which quite aptly sums up the look.

Alva Vanderbilt as “Venetian Princess”

(José Maria Mora, Mrs. William K. Vanderbilt (Alva Murray Smith) as a Venetian Princess at the Vanderbilt Ball, 1883. New-York Historical Society Library.)

The hostess herself came as a “Venetian Princess,” based on a painting by Alexandre Cabanel. Her contemporaries at The New York Times described her dress as having striking hues of brocade from “the deepest orange to the lightest canary” and a light blue satin train with gold embroidery and lined in “Roman red.” Her lavish gown was bedecked in colored gems, making her look like a “superb peacock.”

Other costumes included “Persian Princess,” “Egyptian Princess,” “G*psy Queen,” and Christopher Columbus (terrifying, indeed). Party guests stumbled home as late as 4 a.m. the following morning with aching feet and powdered wigs askew.