I’ve been on a horror film kick. I’ve tortured myself with Kubrick’s classic villains, bloodthirsty cave-dwellers and the slithery eels in Gore Verbinski’s surprisingly good—or is it bad?— thriller, “A Cure for Wellness.” But it’s Jordan Peele’s directorial debut “Get Out” that takes the proverbial cake. It’s a genre-blending experience that proffers genuinely funny moments and relevant social critique in one minute only to turn on a dime and scare the popcorn out of your lap in the next.

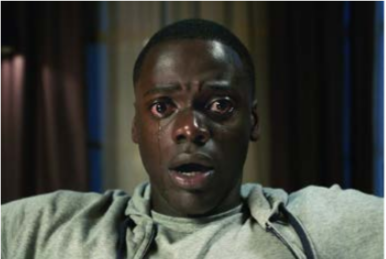

In an effort to avoid spoilers, here’s a quick-and-dirty synopsis: Chris Washington (Daniel Kaluuya) and his white girlfriend Rose Armitage (Allison Williams) visit her frighteningly normal and painfully white parents Missy (Catherine Keener) and Dean (Bradley Whitford). Dean, a neurosurgeon, and Missy, a psychiatrist with a concentration on hypnosis, paint a picture of suburban perfection, one that even Norman Rockwell would be hard-pressed to believe. As idiosyncrasies pile up, Chris becomes increasingly uncomfortable with his obvious blackness until he must fight to the death for his survival in a maelstrom of violence that would make Quentin Tarantino jealous.

By blending the implausible—transmutation, anyone?—with the stark reality of suburban anti-blackness, Peele has managed to capture the 21st-century African-American experience in a horror film that’s being properly lauded for both its merits as a movie and its undisguised politics. Whether it’s of the supernatural or bad cop variety, the audience knows something bad will happen to Andrew, played by Lakeith Stanfield, when he walks down a dark street by himself. This isn’t some dark alleyway in the inner city; it’s a well-lit street in a neighborhood with manicured lawns and cul-de-sacs.

Through the fate of Andrew—from muttering to himself about the street names to being followed by a menacing white sedan to being attacked and stuffed into the sedan’s trunk—Peele winks, grins and sagely nods at the audience. We all know where the scene is going because it’s been seen before in the news and in shared stories on social media.

The slow-burning reality is just as, if not more, scary as an opaque preteen in a lacy white dress. The uneasiness Chris feels at a gathering organized by Missy and Dean, complete with bingo, bocce ball and white cluelessness, cuts through to the audience; we’ve all been somewhere where we’ve stuck out like a sore thumb.

For most, uneasiness is all we feel. For Chris and other African-Americans, the uneasiness can switch to danger in a fatal instant. What’s more, writer-director Peele, most often associated with frequent collaborator Keegan-Michael Key, plays with a much-needed reversal of roles.

The radical inversion of ‘the big scary black guy’ trope, innocent victim and placing Chris in the role of a black man allows him to be scared, emotional, and vulnerable. “Moonlight” started it, but “Get Out” took the defenseless confusion to a whole other level. “Get Out” joins the likes of “The Godfather,” “The Wizard of Oz” and “Toy Story 3” with a rare 99 percent on movie review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes.

Numbers used to define something as subjective as art should always be taken with a grain of salt. The critical acclaim of “Get Out” could be in part attributed to the political climate of the day. But it’s not so much a ‘right time, right place’ situation. Only now can—and should—a horror film be as political as “Get Out.”

It’s a sincere wish of mine that the context of “Get Out” becomes obsolete and as confusing to the next generations as VHS tapes and Sony Walkmans are to ours, because the scariest films are the ones hidden in reality, and in 2017, “Get Out” is as real as it comes.